As would be expected, this has been alluded to in Zohar, Ra’ya Mehimna towards the end of Mishpatim 115a.

Year: 2018

בין-אדם-לחבירו של אנשי צורה

בַּאֲשֶׁר ד’ אִתּוֹ (בראשית ל”ט, כ”ג)

היה זה לפני כעשרים שנה, בהיותי בן 7 בכתה ג! ישבתי ולמדתי עם החברותא שלי בבית הכנסת לדרמן בפרק אלו מציאות [כנהוג למתחילי לימוד הגמרא] והגענו לגמרא המפורסמת באלו מציאות שהמוצא כסות צריך לשטוח אותו כל חודש כדי לאוורר אותו, אולם ההיתר לשוטחה הוא רק לצורך האבידה ולא כאשר נעשה לצורך בעל האבידה כדי להשתמש בו כשטיח בפני אורחים שבאו לצל קורתו, אני והחברותא הסתפקנו בספק “אדיר” מה הדין אם בדיוק ביום השלושים בו הוא חייב לאוורר את הכסות לצורך האבידה הזדמנו בביתו אורחים כך שהוא ירוויח שני הדברים כאחד, כל מי שכף רגלו דרכה אי פעם בחיידר או תלמוד תורה תמה בשעת קריאת שורות אלו מה היה לנו? הרי כל אחד יודע כי שורה לאחר מכן הגמרא בעצמה מסתפקת בזה לצורכה ולצורכו מאי? זו הרי גמרא מפורסמת מאוד, אולם דא עקא כי אנו היינו צעירים נמהרים ולא היה לנו סבלנות להמתין עם שאלתנו וללמוד עוד שורה בגמרא, נוסף על כך בגאוותינו הכרענו בדעתנו שאין אף אחד בבית הכנסת שיכול לפשוט את ספקותינו הגאוניות.

ומכיוון שספק זה היה בעינינו שאלה כה מורכבת, וכה חכמה, עד שהחלטנו שנינו, אני והחברותא, כי שאלה חמורה שכזו אין אחד שראוי לענות לנו ואין ביד אדם מן השורה לפושטה ואחת דינה להיות מוכרעת בלשכת הגזית בביתו של רבינו שר התורה הגר”ח קנייבסקי שליט”א, וממחשבה למעשה קמנו ממקומנו ופנינו אל ביתו של מרן הגר”ח הגר בשכנות לבית הכנסת, את הדלת פתחה לנו הרבנית ע”ה כשהיא שואלת במאור פנים למבוקשינו, לכששמעה שיש באמתחתנו שאלה בלמוד לשאול את הרב, הכניסה אותנו מיד אל הקודש פנימה, חדר לימודו של מרן שליט”א, הגר”ח ישב שם ספון בתלמודו, לכשהבחין בנו שאל בחיוכו הכובש והאבהי לרצוננו, לכששמע את שאלתנו נדהמנו, בבת אחת הפכו פניו לחמורי סבר, משל שמע איזה שאלה נוראית מחמורי עולם, היה זה מחזה מרטיט, פניו האדימו, גידיו בלטו, הפחד נפל על פניו, ונראה היה כי גיהינום פתוחה לפניו, לבסוף לאחר דקה שלימה בה נחרשו קמטיו מתוך מחשבה מאומצת, קבע מרן שליט”א שהוא חושב שמותר… כנראה.. היה ניכר כי הוא אומר את הדברים כמסתפק, ואין בידו תשובה ברורה בעניין.

כשיצאנו מבית מרן שליט”א חשנו חשובים מאוד, אם שאלתנו הטרידה את מחשבתו של מרן שליט”א עד כדי כך, אם מאמץ כה ניכר היה נזקק למי שכל התורה פרוסה לפניו כעל כף ידו בכדי לענות, וגם אחרי מאמץ גדול כזה לא השיב אלא הסתברות בעלמא, משמע, הסקנו – אני והחברותא – גאוני עולם אנחנו ועתידנו לפנינו.

רק כששבנו לבית המדרש והמשכנו עוד שורה בגמרא לצורכה ולצורכו… חפו פנינו, הבן הבנו אל נכון גם בגילנו הכה פעוט, שלא השאלה היא זאת שטרדה את מנוחתו של מרן שליט”א עד כדי כך, אלא הפחד הנורא והמצמית שמישהו כאן, איזה יהודי בן 7 יתבייש, או לחילופין שחלילה נבין ששאלתנו הייתה משובת נעורים מטופשת, הפחד הזה שילד יהודי ירגיש איזה גיחוך ויבין ששאלתו החמורה המהווה את לוז עמלו בתורה היא בעצם ילדות גרידא, פחד זה הוא זה ששיתק את מרן שליט”א שהרגיש את הגהנום של המלבין פני חברו פתוחה לפניו והמאמץ המחשבתי הכביר לא היה אלא מחשבה מעמיקה איך למצוא מוצא לסבך, וגם תוך כדי כך הווה את הפתרון עצמו שע”י המאמץ של המחשבה תינתן לנו תחושה כמי ששאלנו שאלה חשובה המצריכה מאמץ מחשבתי אדיר, הלקח שלימדני מרן שליט”א אז לא ישכח מליבי מהרה, היה זה שיעור נורא הוד בהלכות בין אדם לחברו שראוי לו להילמד עוד ועוד.

מאתר דרשו, כאן.

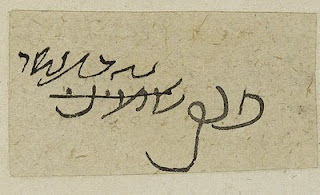

שליחות הרב ישראל משקלוב לבני משה ועשרת השבטים

ניתן לראות את המכתבים בעניין באתר דעת כאן.

Chazal Say: ‘He Who Does Not Work, Neither Shall He Eat!’

Wikipedia ignorantly claims the saying “He who does not work, neither shall he eat” originated from Paul the meshumad, later cited by John Smith in Jamestown, Virginia, and by Lenin during the Russian Revolution.

Actually, the expression comes from holy Chazal in Medrash Rabba (Bereishis Rabba 14:10, Koheles Rabba 2:23, Eicha Rabba 1:43).

Here’s a composite:

ויהי האדם לנפש חיה, …ר’ הונא אמר, עשאו עבד מכודן בפני עצמו, דאי לא לעי לא נגיס. הוא דעתיה דר’ חנינא, דאמר ר’ חנינא, נתנני ה’ בידי לא אוכל קום. בידי לא אוכל קום, אי לא לעי ביממא בלילא לא אוכל קום.

(This Medrash clearly denies the illogical Cursedian view scarcity is a punishment for the sin of Adam Harishon.)

See also Bereishis Rabba 2:2:

רבי אבהו ורבי יהודה בר סימון רבי אבהו אמר משל למלך שקנה לו שני עבדים שניהם באוני אחת ובטימי אחת על אחד גזר שיהא ניזון מטמיון ועל אחד גזר שיהא יגע ואוכל ישב לו אותו תוהא ובוהא אמר שנינו באוני אחת ובטימי אחת זה ניזון מטמיון ואני אם איני יגע איני אוכל כך ישבה הארץ תוהא ובוהא אמרה העליונים והתחתונים נבראו בבת אחת העליונים ניזונין מזיו השכינה התחתונים אם אינם יגעים אינם אוכלים ור’ יהודה בר סימון אמר משל למלך שקנה לו שתי שפחות שתיהן באוני אחת ובטימי אחת על אחת גזר שלא תזוז מפלטין ועל אחת גזר טירודין ישבה לה אותה השפחה תוהא ובוהא אמרה שנינו באוני אחת ובטימי אחת זו אינה יוצאה וזזה מפלטין ועלי גוזר טירודין כך ישבה לה הארץ תוהא ובוהא אמרה העליונים והתחתונים נבראו בבת אחת העליונים חיים והתחתונים מתים לפיכך והארץ היתה תהו ובהו א”ר תנחומא לבן מלך שהיה ישן ע”ג עריסה והיתה מניקתו תוהא ובוהא למה שהיתה יודעת שהיא עתידה ליטול את שלה מתחת ידיו כך צפתה הארץ שהיא עתידה ליטול את שלה מתחת ידיו של אדם שנאמר ארורה האדמה בעבורך לפיכך והארץ היתה תוהו ובוהו.

There’s a brilliant poem quoting the expression, by the way.