The Happiness of Yom Kippur and Succos

by Reuven Chaim Klein

The Mishnah[1] teaches that the days of Tu B’Av (the fifteenth of Av) and Yom Kippur are the two happiest days of the Jewish calendar. The Talmud[2] explains that Yom Kippur is a happy day because it is a day of forgiveness and atonement, and because it is the day on which the second pair of tablets containing the Decalogue was delivered to the Jewish nation on Mount Sinai. Tu B’Av was historically a happy day for various reasons as discussed elsewhere.

Rabbi Yom Tov ben Avrohom Asevilli (1250–1330), also known as Ritva, asks[3] why the Mishnah says that Tu B’Av and Yom Kippur are the happiest days if another Mishnah states:[4] “he who has not witnessed the Simchas Beis HaShoeivah (“The Rejoicing of the Water Drawing”) has not witnessed happiness in his life.” This latter source implies that the Water Libations ceremony in the Holy Temple on the holiday of Succos is the happiest occasion in the Jewish calendar—not Yom Kippur.

The Ritva himself answers that Tu B’Av and Yom Kippur were only happy days for the women of the Jewish people, because on those days they met their future spouses; however, the Simchas Beis HaShoeivah was a happy occasion for all righteous Jews, whether male or female.

Nevertheless, the Ritva’s answer still requires further examination, because the reason for the happiness on Yom Kippur can be apply to men just as to the women, for if the women met their prospective spouses on that day, then, per force, so did the men. Furthermore, of the Talmud’s many reasons for the holiday of Tu B’Av, only one applies specifically to the women.[5] The other reasons given by the Talmud are not limited to the Jewish women to the exclusion of the men. Additionally, Ritva’s answer leaves a gaping ambiguity: according to Ritva, what is the happiest time of the year for the average simple Jew, who is neither righteous nor necessarily female? The Ritva only wrote that the Water Libations ceremony on Succos is a joyous occasion for the righteous Jews, but not for the common man, and Tu B’Av is only joyous for the women, not the men. So what does that leave for the average Jew?

Perhaps one can answer the apparent contradiction between the two Mishnahs by explaining that both Yom Kippur and Succos are the happiest time of the year! We may argue that in some ways, Yom Kippur and Succos can be considered one long period, and the superlative happiness extends throughout this entire period.

The Talmud says[6] that on Erev Yom Kippur, there is a commandment to have a special feast. Rabbeinu Yonah of Girondi (1180–1263) explains[7] that this feast is to express one’s happiness for the holiday of Yom Kippur, because there is no greater happiness than being absolved from all of one’s sins.[8] However, since HaShem decreed that we abstain from food on Yom Kippur, then the happiness of Yom Kippur must be expressed on the day before. Nonetheless, the upshot of this explanation is that Yom Kippur itself is to be considered an especially happy day.

In many communities, Kiddush Levana (a special blessing recited over the newly visible moon) is postponed until Motzei Yom Kippur, so that it can be recited in a happy mood.[9] In a similar vein, HaShem commands that one must “be [nothing] but happy”[10] on Succos. In fact, the numerical value of the Hebrew word selicha (סליחה, forgiveness), equals the value for the word Simcha (שמחה, happiness).[11] This shows that the greatest catalyst for happiness is complete and total forgiveness/atonement. There is no greater happiness than fully knowing that one is completely free from sin. In essence, the theme of Yom Kippur—forgiveness and atonement—is the same as that of Succos—happiness.

The parallel between Succos and Yom Kippur is quite clear. The Talmud says[12] that on Succos, the world is judged concerning its yearly quota of water. In fact, the day after Succos is over, on the holiday of Shemini Atzeres, Jews begin mentioning HaShem’s power to bring rain in their daily prayers. This parallels Yom Kippur on which every Jew’s fate for the year is sealed, and it is one’s final time to repent for sins. The nexus of these judgement is on the last day of Sukkos is known as Hoshana Rabbah (“the Great Salvation”). Extra prayers of repentance and requests for forgiveness are added to the Hoshana Rabbah liturgy, as if to suggest that one’s fate is not completely sealed on Yom Kippur, but rather on Hoshana Rabbah. This is because the motif of Yom Kippur actually continues throughout the festival of Succos, until Hoshana Rabbah.

There are four days in the Jewish calendar, which are known as the Yomim Nor`aim (“Days of Awesomeness”). Namely, they are the two days of Rosh HaShannah, Yom Kippur, and Hoshana Rabbah.[13] Only these four days is the word “awesome” added to the formula, “Our G-d is One, great is Our Lord, [and] holy is His name” recited by the Chazzan when removing the Torah Scrolls from the Ark. Now, the two days of Rosh HaShannah are considered like one long day (Yoma arichta[14]). To maintain the parallelism, one must say that Yom Kippur and Hoshana Rabbah are also to be considered one long period spanning twelve days. This period commences with Yom Kippur and continues through the entire Succos. In fact, immediately after Yom Kippur, one starts preparations for Succos by starting to build the Succah,[15] and Tachanun is not recited in the days between Yom Kippur and Succos, to show that all those days are bridged together by the theme of happiness.[16]

Furthermore, the Hassidic masters teach that each of the seven liquids (enumerated in the Mishnah[17]) that cause a foodstuff to become susceptible to ritual impurity corresponds to one of the seven holidays. According to this model, Dew corresponds to Yom Kippur and Water corresponds to Succos.[18] In essence, dew and water are chemically the same, except that dew is a specific type of water, which falls early in the morning. Similarly, Yom Kippur and Succos are in essence the same, only that Succos is the time for general happiness, while Yom Kippur is the time for the specific happiness stemming from the pardoning of sin.

Rabbi Avrohom Schorr writes[19] that Succos is a time when one is able to “do battle” with HaShem, and harness the power of true repentance to achieve absolution of sin—even in circumstances in which He does not typically grant forgiveness.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev (1740–1810) writes[20] that the repentance during the Ten Days of Repentance from Rosh HaShannah to Yom Kippur is a repentance out of fear (fear from Heavenly punishment and HaShem’s awesomeness), while the repentance achieved during the holiday of Succos is a repentance from love. The difference between the two types of repentance is that repentance from fear only erases one’s sins, while repentance from love transforms one’s sins into fulfillments of positive commandments. It morphs a blot on one’s record into a merit.[21] Thus, Yom Kippur and Succos are simply two means to achieve the same end: the cleansing from sin.

A Jew is commanded to make the pilgrimage to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem three times a year—Pesach, Shavuos, and Succos.[22]When a person enters that holy space, one has a chance to draw from the Holy Spirit, which rested there. However, on the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, a Jew is not commanded to ascend the Temple Mount; rather, he is supposed to stay in his own town and pray wherever he might be. It seems counterintuitive to separate the place that epitomizes holiness (i.e. the Temple) from the time that epitomize such sanctity (that is, Yom Kippur). Why should this be?

Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv (1910–2012) explains[23] that this is because sometimes one is supposed to draw spiritual nourishment from a place, and sometimes, from a time. During the festivals of the pilgrimages, one is expected to draw spiritual nourishment from the place of the Holy Temple,[24] but on Yom Kippur, the spiritual nourishment comes from the day itself. When one sins, even if it is a small sin, that sin accompanies him and draws him to continuing sinning.[25] One sin causes another,[26] and when one sins, other sins appear to become permitted for him.[27] Therefore, even if a person sinned once in his life, he has been initiated into a vicious cycle of sinning, and it is almost inevitable that he will sin again. Therefore, the Day of Yom Kippur itself must come to cleanse one of all sins[28], so that one can stay pure and clean without being subject to the pull of previous sins. This explains why the Talmud says[29] that there is no better day for the Jewish nation than Yom Kippur; it is a day of complete forgiveness and atonement. Only after achieving such a deep cleansing can one be ready to draw from the sanctity of the location of the Holy Spirit in Jerusalem by attending the pilgrimage on Succos. In this way, Yom Kippur simply paves the path towards Succos…

***

Each of the holidays has an additional appellation by which it is described in the Torah and/or in certain liturgical prayers. Rosh HaShannah is also known as Zichron Terua (“A Remembrance of the Shofar Blasts”)[30] because it is the day that the Shofar is blown, Pesach (Passover) is also known as Zman Chayrusaynu (“A Time of Our Freedom”) because it signifies the Jewish exodus from Egypt. In that way, Succos is called Zman Simchasaynu—”A Time of Our Happiness”. What is the source of this special happiness that typifies Succos and no other holiday? On each holiday, there is a commandment to rejoice,[31] so why is only Succos described specifically as a time of happiness?

Rabbi Dovid Povarsky (1902–1999) explains[32] that the happiness on Succos stems from the assurance that the judgment passed on Rosh HaShannah concluded with a favorable verdict. Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher Ba’al HaTurim (1270–1340) similarly writes[33] that is the meaning of the verse, “Go eat your bread in happiness and drink your wine in good heartedness because G-d has approved of your deeds.”[34] HaShem absolving our sins is the greatest reason for happiness.

Indeed, the Midrash explains[35] that the Holy Temple is described as the “happiest [place] in the entire world” (sorry Disneyland), because as long as the Holy Templestood, no Jew was ever despondent. This was because when a Jew would simply enter the Holy Temple in a state of sinfulness, he would then offer sacrifices and be forgiven of his sins. The Midrash concludes that there is no greater happiness than one who was pronounced innocent in judgment, and this is why the Holy Temple is called “the happiest place on earth.”

Perhaps one can add, as Rabbi Elyashiv insinuated above, that Succos is a happy day squarely because of its location (because people are in a Sukkah, or in Jerusalem, or in their Synagogue), while Yom Kippur does not signify happiness of place, but happiness of time (because the day of Yom Kippur itself creates happiness by bringing forgiveness). It is perhaps for this reason why there is a custom amongst many Jews to sing and dance immediately following the N`eilah services at the conclusion of Yom Kippur.

Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Braun (d. 1994) offers another twist on this idea. He writes,[36] based on Rashi,[37] that when one’s sins are atoned, one is especially joyous. This is the basis for the words of the above-cited Midrash[38] that applies the verse “Go eat your bread in happiness”[39] to the night after Yom Kippur. Throughout the entire day of Yom Kippur, the Jews fast and ask for His forgiveness. After that pardon is granted, a heavenly voice calls out to the Jews, “Go eat your bread in happiness.” This explains the opinion of Tosafos[40] who write that on the night after Yom Kippur, there is a special commandment to eat a festive meal. This obligation stems from the fact that after Yom Kippur, there is an extra special sense of happiness stemming from the forgiveness of sins.[41]

The happiness on Yom Kippur is a sort of controlled happiness. The rejoicing on Yom Kippur should be a rejoicing while shaking in fear of what His judgment might entail. About this, the Psalmist writes, “…And rejoice with trembling.” [42]

Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv says that the verse customarily said before Kol Nidrei on Yom Kippur Eve is a prime example of this type of rejoicing. That verse reads: “The light is sown for the righteous, and for those of an upright heart, happiness.” [43] The happiness in this verse refers to the happiness on Yom Kippur that comes from the atonement of sin, hence it is associated with the “righteous” and “upright.” In fact, The Mishnah in the end of the Tractate Yoma (which deals with the laws of Yom Kippur and the Temple services on that day) says that just a Mikvah purifies the impure; so does HaShem purify Israel from their sins. This is the happiness of Yom Kippur.

In a similar vein, we find that the happiness of Succos is also related to the cleansing from sin. The Talmud says[44] that at the Simchas Beis HaShoeivah on Succos, the pious men would dance and declare how happy they are that they did not sin in their youth, because it would embarrass them in their old age. Meanwhile, the penitents would dance singing that they are happy that their older years serve as atonement for the sins of their younger years. Both groups of men would join for the refrain, mutually agreeing that “happy is one who did not sin.” This shows that even the happiness of Succos comes from being free of sin—a direct result of the atonement achieved on Yom Kippur.

In describing the commandment of Lulav and Esrog on Succos, the Torah says, “And you shall take for yourselves, on the first day, the fruit of a citron tree, branches of date palms, twigs of plaited [myrtle] trees, and brook willows, and you shall be happy in front of HaShem, your G-d, for seven days.” [45]

The other holidays listed in the same passage are referred to by their date in the month. This leads the Midrash to ask[46] why the Torah calls the first day of Succos “the first day,” if it is actually the fifteenth day of the month, not the first. The Midrash answers that Succos is called “the first day” because it is “the first day” since the accounting of sins. This means that one’s slate is cleared on Yom Kippur and he begins anew on Succos. During the days between Yom Kippur and Succos, no one can possibly sin because everyone is so busy preparing for upcoming holiday; but once the holiday arrives, the new accounting of sins for the year can begin.[47] (Rabbi Elyashiv asks whether this reasoning applies in present times, for who is to say that they remained completely free of sin between Yom Kippur and Succos.)

Rabbi Elyashiv reiterates the point that the entire happiness on Succos is a result of the atonement of sins from Yom Kippur, five days earlier. This explains why in the Talmud’s description of the Simchas Bais HaShoeivah that all the songs sung concerned repentance and freedom from sin.

***

The Torah relates an episode in which the Jews in the desert demanded from Moses that he provide them with meat (after having eaten only manna until then). When HaShem told Moses about the fatty birds that He intended to feed the Jewish People, He said, “Not for one day shall you eat it, nor for two days, nor for five days, not for ten days, not for twenty days, [rather] a month.”[48]

The Tosafists explain the significance of these various intervals of days that HaShem specified.[49] They explain HaShem meant to stress that He will not send the fatty birds for a certain interval of time for which there is already a precedent of happiness and celebration, but will instead send the birds for a hitherto unexperienced interval of thirty days. The Tosafists then explain how each of the numbers stated represent a significant set of days on the Jewish Calendar: “one day” refers to Yom Kippur, “two days” refers Rosh HaShannah or Shavous, “five days” refers to the five days from Yom Kippur to Succos, “ten days” refers to the Ten Days of Repentance between Rosh HaShannah and Yom Kippur, and “twenty days” refers to the twenty-one days on which the entire Hallel is recited.[50] From the Tosafists’ explanation one sees that the five-day period spanning from Yom Kippur to Succos is considered one long continuation of happiness.

We see this in another context as well: The Talmud[51] writes that the word “the Satan” equals in gematria three hundred and sixty-four, alluding to the fact that the Satan only maintains his accusatory powers for three hundred sixty-four days a year, but for one day a year he remains powerless: Yom Kippur.

Rabbi Chanoch Zundel of Bialystock (d. 1867) asks in the name of Rabbi Yehonasan Eyebschitz (1690–1764) the following question:[52] While the numerical value of “the Satan” equals three hundred and sixty-four, the Satan’s name is not “the Satan,” as the word “the” is not part of his name; it is simply the definite article and serves a grammatical function. Rather, his name is “Satan” which only equals three hundred and fifty-nine, so how does this jive with the Talmud’s exegesis concerning the number of days on which the Satan has permission to prosecute?

In his conclusion, Rabbi Chanoch Zundel ultimately concurs with the basic premise of the question, and instead readjusts what the Talmud says. Essentially, he asserts that the Satan remains powerless for an additional five less days not mentioned in the Talmud: the five days between Yom Kippur and Succos. This again shows us that the period between Yom Kippur and Succos is viewed as one long continuation, spanning all the days in between the two holidays as well. This can be understood based on the abovementioned principle that the happiness of Succos is attributable to the exoneration and absolution of sin as introduced by Yom Kippur.

***

I would like to suggest that perhaps we can take this discussion in another direction. Perhaps we can argue that the happiness on Succos directly results from the sealing of one’s fate on Yom Kippur. A popular Hebrew dictum states, “There is no happiness like the answering of a doubt.”[53] Indeed, the feeling of doubt is potentially the most negative and destructive emotion possible. Uncertainty can cause one to resort to drastic measures as a means of achieving closure.

In fact, a famous Hassidic lesson related in the name of the Ba’al Shem Tov, Rabbi Yisroel ben Eliezer (1698–1760) illustrates this very point. He explains that the numerical value of the Hebrew word for “doubt” (ספק, safek) equals that of the word “Amalek” (עמלק), because just as Esau’s grandson Amalek can attack a person and adversely affect one’s sanity through his venom of cloudiness, so does a doubt hit at the core of a person’s functionality to destroy him from the inside. Accordingly, it serves to reason that there can be no greater feeling than the feeling of relief in answering a doubt.[54]

The Talmud[55] states that on Rosh HaShannah those who are completely righteous are written and sealed with a favorable judgment, and the those who are completely wicked, the opposite. But everyone in between completely righteous and completely wicked remains in a state of limbo until Yom Kippur—at which time they are judged according to their actions and are finally written and sealed. This state of limbo which representation the Divine indecision about one’s fate is surely the worst situation in which one can be. With this in mind, we can now appreciate the happiness of Yom Kippur. When all of one’s sins are forgiven, one can finally rest-assured that HaShem’s judgment concluding favorably and can now revel in the happiness of knowing that his destiny has been finalized. This finality serves as the underlying reason for the happiness of Yom Kippur and the subsequent days including Succos.

In the beginning of this essay, we cited the Ritva’s question who notes that the Mishnah seems to contradict itself concerning the happiest time of the year. Is the happiest time of the year Yom Kippur/Tu B’Av, or is it Yom Kippur? In light of the above, the entire question is moot. We now understand that the happiness of Succos and Yom Kippur are indeed one and the same, and indeed they are the same as Tu B’Av.

The joy of Tu B’Av originated in the fortieth year of the Jews’ travels in the desert, when every year on Tisha B’Av, all the Jews slept in a grave and a segment of that population would not wake up the next morning. However, in the fortieth year, every person woke up on Tisha B’Av morning; no one died that year. The Jews assumed that they must have miscalculated the date, and they performed the same rite the next day. Yet, even the next night, no one died. They again assumed that they erred in calculating the date, and this continued until they saw the full moon on the fifteenth of the month at which point they know with certainty that Tisha B’Av had passed a no one died. This was the main cause for celebration on Tu B’Av.

This explanation also conveys the idea of rejoicing at the resolution of an uncertainty, for each night until Tu B’Av every man who slept in his grave was uncertain whether the next day he would wake up or not. But from Tu B’Av and onwards, he knew that he would survive. Therefore, the root of the happiness on Yom Kippur and Succos, which is based on the finality of HaShem’s judgement and the clearing away of uncertainty, matches the underlying basis for the happiness of Tu B’Av.

May HaShem forgive His nation from all of their sins so that we may merit the rebuilding of the Holy Temple, speedily and in our days and we should be able to appear before Him pure,[56] and continue the thrice-yearly pilgrimages to Jerusalem: Amen.[57]

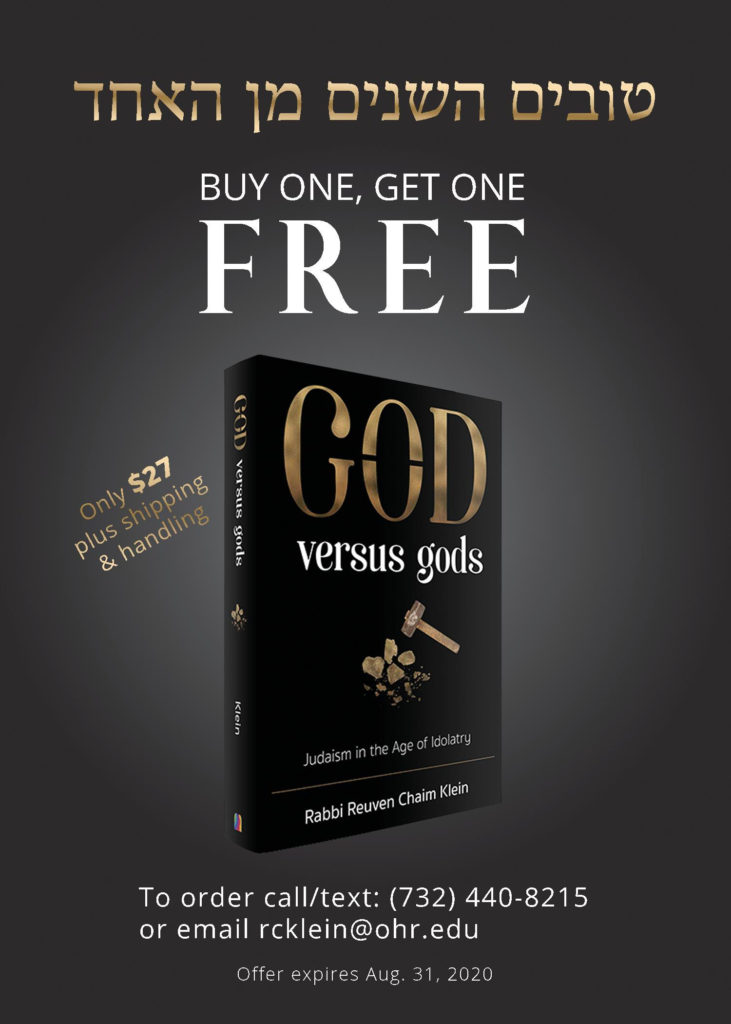

* Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein is the author of God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry (Mosaica Press, 2018), a scholarly study on all the stories related to the struggle against idol worship in the Bible. He is the founding editor of the Veromemanu Foundation for the study of Hebrew etymology and is also a freelance editor/translator/researcher. He lives with his wife and children in West Bank city of Beitar Illit. He originally penned this essay as a teenager and recently made some slight editorial revisions.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] In the end of Tractate

Taanis.

[2] Taanis 30b.

[3] Chiddushei HaRitva to Bava Basra 121a.

[4] Sukkah 51a.

[5] That is, according to the reason that Tu B’Av is a joyous day because it allowed women who inherited real property to marry men from tribes other than their father’s tribe (see Pnei Shlomo to Bava Basra 121a).

[6] Rosh HaShannah 9a.

[7] Sha’arei Teshuvah 4:8-9.

[8] He also explains that the feast is in order to make easier the next day’s fast. See responsa Maharit (vol. 2, Orach Chaim, §8) who writes the exact opposite, i.e. that the feast is in order to make the next day’s fast more difficult. See also Chiddushei HaRitva (to Rosh HaShannah 9a) who mentions another explanation in the name of Rabbeinu Yonah of Girona.

[9] See Rema to Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim §602:1).

[10] Deuteronomy 16:15.

[11] Assuming that the letters sin and samech are interchangeable because they make the same sound.

[12] Taanis 2a.

[13] Although, according to Rabbeinu Yonah (Sha’arei Teshuvah 2:5) all Ten Days of Repentance from Rosh HaShannah to Yom Kippur are considered Yomim Nor`aim.

[14] See Beitzah 30b.

[15] Rema to Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim, end of §624.

[16] Rema to Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim §624:5.

[17] Machshirin 6:4

[18] The other five liquids are: Oil (Chanukah), Wine (Purim), Blood (Pesach), Milk (Shavuos), Honey (Rosh HaShannah).

[19] HaLekav V’HaLibuv.

[20] Kedushas Levi.

[21] See Yoma 86b.

[22] Deuteronomy 16:16.

[23] Divrei Aggadah.

[24] Tosafos to Succah 50b says that the Simchas Beis HaShoeivah is called so because one “draws” holiness in spirituality from HaShem’s presence, which rested at Holy Temple.

[25] Sotah 3b.

[26] Avos 4:2.

[27] Yoma 86b.

[28] Leviticus 16:30.

[29] Taanis 30b.

[30] Leviticus 23:24.

[31] E.g. see Deuteronomy 16:11.

[32] Yishmiru Da’as, Chol HaMoed Succos 5756.

[33] Tur, Orach Chaim §624.

[34] Ecclesiastes 9:7.

[35] Exodus Rabbah 36:1.

[36] Shearim Mitzuyanim B’Halacha to Bava Basra 48a.

[37] To Menachos 20a.

[38] Ecclesiastes Rabbah.

[39] Ecclesiastes 9:7.

[40] To Yoma 87b.

[41] Throughout Rabbinic literature, Succos is referred to as simply HaChag (“the holiday”). The numerical value of the Hebrew word “Chag” is eleven. Perhaps one may conjecture that the significance of the number eleven in this context is that it is the number immediately after ten. Ten is the day of the month of Tishrei on which Yom Kippur is observed. The fact that Succos is associated with the number eleven reveals a connection that Succos has with Yom Kippur which immediately precedes it.

[42] Psalms 2:10.

[43] Psalms 97:11.

[44] Sukkah 53a.

[45] Leviticus 23:40.

[46] Tanchuma, Emor §22.

[47] Yalkut Shimoni, Torah §651, see also Tur, Orach Chaim §581.

[48] Numbers 11:19.

[49] Da’as Zekanim to Numbers 11:19.

[50] That is, eight days of Chanukah, the first two days of Pesach, the first seven days of Succos, the two days of Shavous, the two days of Shemini Atzeres and Simchas Torah.

[51] Nedarim 32a.

[52] Eitz Yosef to Yoma 20a.

[53] See Metzudas Dovid to Proverbs 15:30.

[54] Maharam Schiff in Drashos Nechmados (back of Chullin, Pashas Nitzavim) writes that the fact that Deuteronomy’s rebuke consists of 98 revealed curses and two unknown curses bothered the Jewish People so much because the possible effects of those two unknown curses scared them to their wits.

[55] Rosh HaShannah 16b.

[56] Leviticus 16:30.

[57] Deuteronomy 16:16.