After their long journey in the desert, the people of Israel arrived at the east side of the Jordan River, near the Dead Sea, where the Biblical nation of Moab was located. The Book of Numbers tells the story of Balaam ben Beor, the non-Jewish prophet from the city of Pethor. Balaam was hired by Balak, king of Moab, to curse the Jewish people who were approaching his land, since Balak was fearful that after they had smitten the Amorites, they would go on to conquer Moab:

The children of Israel journeyed and encamped on the plains of Moab, across the Jordan from Jericho… Balak the son of Tzippor was king of Moab at that time. He sent messengers to Balaam the son of Beor… to call for him, saying, “Please come and curse this people for me, for they are too powerful for me. Perhaps I will be able to wage war against them and drive them out of the land, for I know that whomever you bless is blessed and whomever you curse is cursed.”) Numbers 22:1-6(

The Bible describes Balaam’s unsuccessful attempts to curse Israel, which turned into blessings and glowing praises of the Jewish people. Ultimately, Balak became incensed with Balaam and drove him away in disgrace.

In 1967, archaeologists discovered in Transjordan, not far from the mountains of Moab, an ancient inscription they called “Balaam’s inscription.” Balaam’s name appears in it, and the contents are highly reminiscent of the story told in the Bible about Balaam.

The inscription was discovered when archaeologists from the Netherlands conducted excavations in Tel Deir ‘Alla in Transjordan. In a sanctuary dating from the eighth century B.C.E. that they exposed there, they found fragments of ancient inscriptions written on plaster in red and black ink.

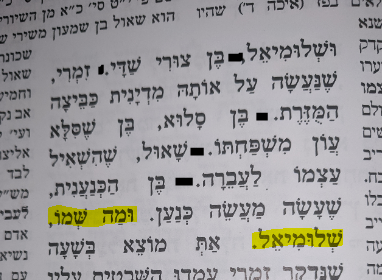

After decryption, the researchers were surprised to discover that the inscriptions describe a prophet called “Balaam bar Ber” (in Aramaic: ben Beor) “a man who can envision God,” who sees in his prophecy that which will occur at the end of days. This inscription is today in a museum in Rabbat Amman, and is dated to 760-880 B.C.E.

The inscription contains details about Balaam that are very close in content and terminology to the Biblical story:

The inscription tells of Balaam’s agony: “And for two days he fasted, and wept bitterly… Then his intimates entered and asked, ‘Why do you fast, and why do you weep?’” This description matches what the Bible tells us of Balaam’s inner turmoil when he initially received an order from God to refrain from joining Balak’s emissaries. Balaam felt great anguish over it because he longed to fulfill the evil mission that Balak wanted him to undertake.

Here we have unique archaeological testimony about the figure of Balaam who appears in the Bible. The details that appear in it, including the geographical location and the historical period, closely approximate the Biblical account of what happened in the mountains of Moab, opposite the approaching camp of the Israelites.

Adapted from ‘Hidden Treasures – Archaeology Discovers the Hebrew Bible’ by Rabbi Zamir Cohen.

Click here to buy