Perhaps not since the nineteenth century have so many American voters so fervently doubted the outcome of a national election.

A Slate headline from December 13 reads: “82 Percent of Trump Voters Say Biden’s Win Isn’t Legitimate.” If even half true, this poll means tens of millions of Americans believe the incoming ruling party in Washington got its political power by cheating.

The implications of this are broader than one might think. Under the current system, if many millions of Americans doubt the veracity of the official vote count, the challenge to the status quo goes beyond simply thinking that Democrats are cheaters. Rather, the Trump voters’ doubts indict much of the American political system overall and call its legitimacy into question.

For example, if Trump supporters are unwilling to accept that the vote count in Georgia was fair—in a state where Republicans control both the legislature and the governor’s mansion—this means skepticism goes well beyond mere distrust of the Democratic Party. For Trump’s vote-count skeptics, not even the GOP or the nonpartisan election officials can be trusted to count the votes properly.

Moreover, unlike the general public, Trump supporters appear to have adopted a keenly suspicious view toward these administrators and the systems they control. This is all to the best, regardless of the true extent of voter fraud in 2020. After all, government administrators—including those who count the votes—are not mere disinterested, efficiency-obsessed administrators. They have their own biases and political interests. They’re not neutral.

Trump as Outsider

How did Trump supporters become such skeptics? Whether accurately or not, Trump is viewed as an antiestablishment figure by most of his supporters. He is supposed to be the man who will “drain the swamp” and oppose the entrenched administrative state (i.e., the deep state).

In practice, this means opposition must go beyond mere partisan opposition. It was not enough to simply trust the GOP, because, either instinctively or intellectually, many Trump supporters know he has never really been a part of the GOP establishment. The opposition from within the Republican Party has always been substantial, and the old party guard never stopped opposing him. For Trump’s supporters, then, the two-party system isn’t enough to act as a brake on abuse by the administrative state—at least when it comes to sabotaging the Trump administration. In the minds of many supporters, Trump embodies the anti-establishment party while his opponents can be found in both parties and in the nonpartisan administrative state itself.

This view has formed over time in a reaction to real life experience. Trump supporters have been given plenty of reasons to suspect that anti-Trump sentiment is endemic within the bureaucracy. For example, from the beginning, high-ranking “nonpartisan” officials at the FBI were actively seeking to undermine the Trump presidency. Then there was Alexander Vindman, who openly opposed legal orders from the White House and lent aid to House officials hoping to impeach Trump. Then there were those Pentagon officials who apparently lied to Trump in order to avoid drawing down US troops in Syria. All this was on top of the usual bureaucrats, who already tend to be hated by conservative populists: education bureaucrats, IRS agents, environmental regulators, and others responsible for carrying out federal edicts.

And then there were the federal medical “experts” like Anthony Fauci, who insisted Americans ought not to be allowed to leave their homes until no new covid-19 cases were discovered for a period of weeks. Translation: never.

Health technocrats like Fauci came to be hated by Trump supporters, not just for seeking to shut down churches and ruin the lives of countless business owners, but for setting themselves up as political opponents of the administration through daily press releases and other means of contradicting the White House.

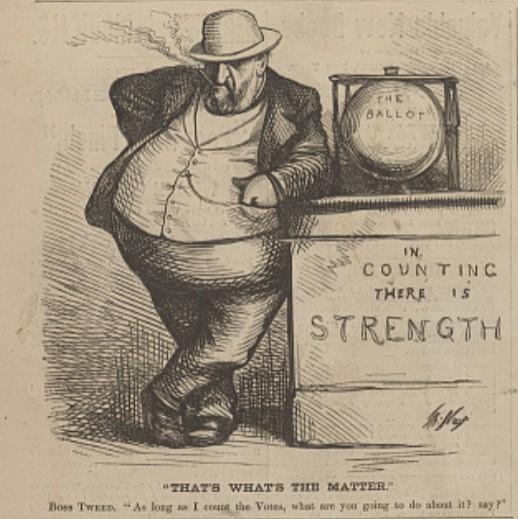

It only makes sense that Trump’s supporters would extend this distrust of the bureaucracy to those who count the votes. After all, who counts the votes has always been of utmost importance. It’s why renowned political cartoonist Thomas Nast had Boss Tweed utter these words in an 1871 cartoon: “As long as I count the votes, what are you going to do about it?”

This has always been a good question.

Old party bosses like Tweed are now out of the picture, but the votes nowadays are calculated and certified instead by people who, like Tweed, have their own ideological views and their own political interests. The official vote counts are handed down by bureaucratic election officials and by party officials, most of whom are outside the circles of Trump loyalists.

Given the outright political and bureaucratic opposition Trump has faced from other corners of the administrative state, there seems to be little reason for his supporters to trust those who count the votes.

Learning to Mistrust the Administrative State

Thus, whether facing FBI agents or election officials, Trump supporters learned to take official government reports and pronouncements with a healthy dose of skepticism. The end result: for the first time, under Trump, the American administrative state came to be widely viewed as a political force seeking to undermine a legitimately elected president, and as a political interest group in itself.

Naturally, the media and the administrative state itself have reacted to this with outrage and disbelief that anyone could believe that the professional technocrats and bureaucrats could have anything in mind other than selfless, efficient service to the greater good. The idea that lifelong employees of the regime might be biased against a man supposedly tasked with dismantling the regime was—we were assured—absurd.

Civil Service Reform and the Rise of the Permanent Bureaucracy

Although Trump’s supporters may get some of the details wrong, the distrustful view of the bureaucracy is the more accurate and realistic view. The view of the American administrative state as impartial, nonideological, and aloof from politics has always been the naïve view, and one pushed by the Progressive reformers who created this class of permanent government “experts.”

Before these Progressives triumphed in the early twentieth century, this permanent class of technocrats, bureaucrats and “experts” did not exist in the United States. Prior to civil service reform in the late nineteenth century, most bureaucratic jobs—at all levels of government—were given to party loyalists. When Republicans won the White House, the Republican president filled bureaucratic positions with political supporters. Other parties did the same.

This was denounced by reformers, who maligned this system as “the spoils system.” Reformers insisted that American politics would be far less corrupt, more efficient, and less politicized, if permanently appointed experts in public administration were put into these positions instead.

The Administrative State as an Interest Group

But the rub was that in spite of claims by the reformers, there was never any reason to assume this new class of administrators would be politically neutral. The first sign of danger in this regard was the fact that those who wanted civil service reform seemed to come from a very specific background. Murray Rothbard writes:

The civil service Reformers were a remarkably homogeneous group. Concentrated almost exclusively in the urban Northeast, including New York City and especially Boston, the Reformers virtually constituted an older, highly educated and articulate elite. From families of old patrician wealth, mercantile and financial rather than coming from new industries, these men despised what they saw as the crass materialism of the nouveau riche, as well as their lack of good breeding or education at Harvard or Yale. Not only were the Reformers merchants, attorneys, and educators, but they virtually constituted the most influential “media elite” of the day: editors, writers, and scholars.

In practice, as Rothbard has shown, civil service reform did not eliminate corruption or bias in the administration of the regime. Rather, the advent of the civil service only shifted bureaucratic power away from working-class party loyalists, and toward middle-class and university-educated personnel. These people, of course, had their own socioeconomic backgrounds and political agendas, as suggested by one anti-reform politician at the time who recognized that civil service exams would be employed to direct jobs in a certain direction:

So, sir, it comes to this at last, that…the dunce who had been crammed up to a diploma at Yale, and comes fresh from his cramming, will be preferred in all civil service appointments to the ablest, most successful, and most upright business man of the country, who either did not enjoy the benefit of early education, or from whose mind, long engrossed in practical pursuits, the details and niceties of academic knowledge have faded away as the headlands disappear when the mariner bids his native land good night.

Gone were the old party activists who had worked their way up to a position of power from local communities in which they had skin in the game. The new technocrats were something else entirely.

Today, of course, the bureaucracy continues to be characterized by ideological leanings of its own. For example, government workers, from the federal level down, skew heavily Democrat. They have more job security. They’re better paid. They’re less rural. They have more formal education. It’s a safe bet the bureaucracy isn’t chock full of Trump supporters. Civil service reform didn’t eliminate corruption and bias. It simply created a different kind.

Trump supporters recognize that these people don’t go away when “their guy” wins. These are permanent civil “servants” whom Trump supporters suspect—with good reason—have been thoroughly opposed to the Trump administration.

So, if the FBI and the Pentagon have already demonstrated their officials are willing to break and bend rules to obstruct Trump, why believe the administrative class when they insist elections are free and fair and all above board? Many have found little reason to do so.

From Mises.org, here.