[CORRECTED] Jewish Surnames Explained

Correction, Jan. 29, 2014: Some of the sources used in the reporting of this piece were unreliable and resulted in a number of untruths and inaccuracies. The original post remains below, but a follow-up post outlining the errors, as well as further explanation, can be found here.

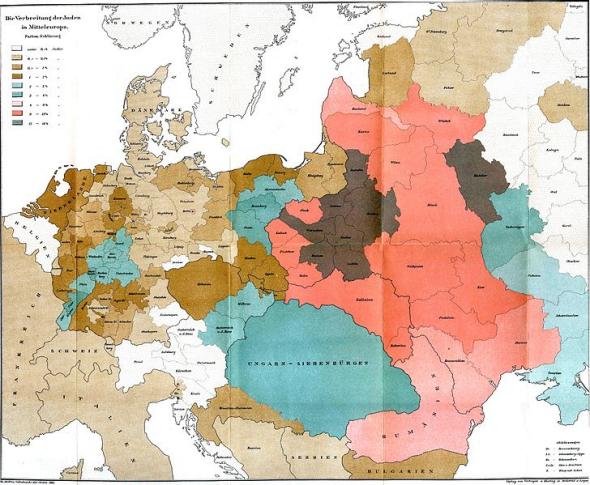

Ashkenazic Jews were among the last Europeans to take family names. Some German-speaking Jews took last names as early as the 17th century, but the overwhelming majority of Jews lived in Eastern Europe and did not take last names until compelled to do so. The process began in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1787 and ended in Czarist Russia in 1844.

In attempting to build modern nation-states, the authorities insisted that Jews take last names so that they could be taxed, drafted, and educated (in that order of importance). For centuries, Jewish communal leaders were responsible for collecting taxes from the Jewish population on behalf of the government, and in some cases were responsible for filling draft quotas. Education was traditionally an internal Jewish affair.

Until this period, Jewish names generally changed with every generation. For example, if Moses son of Mendel (Moyshe ben Mendel) married Sarah daughter of Rebecca (Sora bas Rifke), and they had a boy and named it Samuel (Shmuel), the child would be called Shmuel ben Moyshe. If they had a girl and named her Feygele, she would be called Feygele bas Sora.

Jews distrusted the authorities and resisted the new requirement. Although they were forced to take last names, at first they were used only for official purposes. Among themselves, they kept their traditional names. Over time, Jews accepted the new last names, which were essential as Jews sought to advance within the broader society and as the shtetles were transformed or Jews left them for big cities.