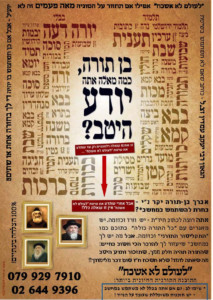

הפתרון לשכחת התורה? – קורס ותוכנה

בעזה”י

שלו’ וברכה מתוככי ירושלם תוב”ב.

ידיעת התורה של מה שלמדנו הוא הערך *היותר עליוני* בחיים של כל יהודי אמיתי. אבל הפעם אנחנו לא *נדבר* על חשיבות של ידיעת התורה שלמדנו, אבל גם נציע *פיתרון יעיל* לצורך זה – *ועוד איך הוא יעיל*!

הפתרון נקרא “לעולם לא אשכח פקודיך” והוא גובש ופותח על ידינו בס”ד עצומה.

לעולם לא אשכח פקודיך הוא כולל שני דברים: *קורס* *ותוכנה*.

הקורס הוא ארבע שעות של שמיעת שיעורים:

החומר בקורס הזה הוא פרי של 25 שנה של מחקר וחיפוש בדברי רבותנו ז”ל למשך הדורות אחרי הדרכה *איך ללמוד* *ואיך לחזור* בצורה ש*תבטיח* שלא נשכח תלמודנו.

ואחרי שנים אלה אספנו את כל הידע שמצאנו ועשינו מכל הדברים *סדר בר עשייה* שפשוט *עובד*.

*עיקרי הדברים הם על פי החפץ חיים חיים, החתם סופר, האור שמח, והסטיילער זכר כולם לברכה – ובעיקר על פי רבי יעקב עמדין ז”ל (היעב”ץ ז”ל) שכותב שמי שמשתמש בשיטה הזאת יוכל להסתפק *בחזרה אחת או שתים* ומי שלא משתמש בו *אפילו מאה חזרות לא יועילו לו*.

שמעתם?!!!!

עם השיטת “לעולם לא אשכח” *חזרה אחת או שתים* ובלי השיטה *אפילו מאה פעמים לא יועילו לו*. אינך צריך להיות פרופסור למתימתיקה לעשות החשבון מהו ההבדל בין *אחת או שתים* ל*מאה פעמים*.

אבל חוץ מהקורס יש עוד דבר נפלא מאד והיא תוכנת מחשב גאונית *בנויה על פי עיקרונות הקורס* ש*משגיח עליך* שלא תשכח שום דבר מהלימוד שלך.

קצת קשה להסביר איך זה עובד, אבל אחרי שמיעת השיעורים של הקורס – התוכנה ממש מובנת מאליה – *אבל עוצמתה אי אפשר לשער ולתאר*!

הלא תסכים שכבר הגיע הזמן שאחרי שעות של לימוד בשקידה נוכל *לתפוס תלמודנו בידינו*

התושה שאכן הזמן הגיע. הגיעה הבשורה המרננת שהיום תוכל להנות מידיעות רחבות מש”ס ופוסקים – משנה ברורה – שו”תים *וכל הספרים*!

אי אפשר לשער את *האושר* שיש למי שזוכר ויודע תלמודו. ואכן המון אנשים אמרו וכתבו לנו ש”לעולם לא אשכח פקודך *שינה את כל החיים לטובה*

ובכן תתקשר עכשיו בארץ ישראל: 0799297910 או בארצות הברית 1-800-220-7505 או שלח לנו מייל בחזרה ואנחנו נייצור אתך קשר בקרוב.