Did You Know Cursedian Zionism Preceded Secular Zionism?

An overview of how Hashem paved the way by Dispensationalism…

An overview of how Hashem paved the way by Dispensationalism…

מנהיג הליכוד וראש הממשלה בעבר, ואולי גם בעתיד, בנימין נתניהו, הגיע לשבע ברכות אצל נכדתו של ח”כ הרב משה גפני. ביקור נימוסין של פוליטיקאי ותיק אצל חברו, הותיק לא פחות. אירוע שגרתי למדי. אך מה שהתחולל מחוץ לבית בו נערכה השמחה, ושמא היה זה אולם, איני יודע – ראוי לתשומת לב יתרה. סרטון קצר שהופץ מראה גלי הערצה של הציבור הבני-ברקי כלפי המנהיג גלוי-הראש, שאמנם יודע לכבד ולכן הגיע עם כיפה שחורה לאירוע. האנשים שהופיעו שם נראו כבחורי ישיבות וסתם יהודים חרדים רגילים לחלוטין. לא שוליים, לא נושרים, לא שום דבר יוצא דופן. גם לא נראה כלל, כי היה כאן משהו מאורגן. מפה לאוזן עברה השמועה, כי ‘ביבי מגיע’, והקהל הריע בהמוניו, תוך שהמנהיג הנערץ מנופף להם בידו. אין הרבה גדולי תורה שזוכים לכזו הערצה, והתופעה אמורה לעורר בקרב כל אנשי החינוך סימני דאגה לא מעטים. ואכן, ב’יתד נאמן’ מהרו לפרסם מכתב ישן מהגרח”ש קרליץ, אשר עוסק בנושא זה של חנופה לרשעים, ואשר נכתב עקב תופעה דומה שהיתה בזמנו. ואמנם כל מילה במכתב היא אמת לאמתה, אך אין ביכולתם של דברים אלו להתמודד כלל עם הבעיה, ונראה כי רוב הציבור כלל אינו תופס מהי.

ניתן בהחלט להלין על ירידת הדורות, ועל הרדידות והשטחיות שנגרמות עקב פגעי הטכנולוגיה וחדירתה לתוככי ציבור היראים. אולם בכך לא נפתור את שורש הבעיה. ושורש הבעיה הוא הפער שנוצר בין מציאות חיינו כאן בארץ אחר 74 שנות קיומה של מדינת ישראל לבין דרכי ההתמודדות שהיו נכונות בעבר, אך כיום אינן מצליחות לעצור את הסחף לעבר הערצת דמויות חילוניות בעלות עוצמה, ובראשן נתניהו.

גדל כאן דור של בחורי ישיבות, חלקם למדנים ומתמידים לא פחות ואף יותר מבדורות הקודמים, אך שונים במהותם מבני הדור הקודם. מדובר בנוער חרדי שגדל כאן בארץ, שהוריהם גדלו כאן בארץ, שהמציאות היחידה שהם מכירים היא של עם ישראל הנמצא בארצו, שולט בגורלו ואינו נתון לחסדי האומות. הסיפורים על הקוזקים והקנטוניסטים, האינקוויזיציה והשואה, הרדיפות והפוגרומים שעמנו סבל מהם במשך כל שנות גלותו – סיפורים אלו הם עבורו נחלת העבר, חומר ללימוד היסטוריה או להשתעשעות בסיפורי קומיקס. המציאות בה הוא חי היא של ארץ פורחת לאורך, לרוחב ולגובה, ישובים קמים, בנינים מגרדים את השחקים, מכוניות שועטות בכבישים במשך כל שעות היממה, מפעלים מייצרים כל מה ששווה לייצר, תעשיית ההיי-טק הישראלית מתחרה במדינות המפותחות בעולם, ואף מצליחה לגבור עליהן, מערכת הבריאות הולכת ומשתכללת ומחירי הדירות מרקיעים שחקים, שזה אמנם מקשה על קנית דירה, אך זה מעיד בהחלט על עוצמתה של ישראל מבחינה כלכלית. בעיראק יותר קל לקנות דירה… .

את כל הדברים האלו מייצג בנימין נתניהו. לא הרב משה גפני. גם לא גדולי ישראל. הם מייצגים את עולם הרוח, עולם שהוא ללא ספק נעלה יותר, וככל שהיהודי יותר ספון בעולמה של תורה הוא מבין זאת יותר ומעריך זאת יותר. אבל העולם הזה נראה כמנותק מכל מה שקורה ‘בחוץ’. אך מה לעשות, והאדם מורכב מחומר ורוח, מגוף ונפש, וגם בחור הישיבה המתמיד ביותר מכיר בצרכיו החומריים, ואחר שהתורה וחכמיה הפכו לנציגי הרוח בלבד – הפכו בנימין נתניהו וההיי-טק הישראלי לנציגי החומר. ולכן ניתן בישיבות רבות למצוא תמונות של נתניהו על קירות הפנימיה, לא בהיכל הישיבה חלילה, אבל בהחלט במקומות בהם אין יד המשגיח מגעת. ולכן כשנתניהו מגיע לבני-ברק, הוא מתקבל באהדה לא פחות מאשר בשוק מחנה יהודה, ואולי קצת יותר.

מה ניתן לעשות? הפתרון טמון בהבנת הבעיה. עלינו להבין, כי תורתנו תורת חיים היא, היא אינה איזו פילוסופיה גבוהה, איזו חוויה רוחנית המנותקת מהמציאות, כי אם להפך – היא המנתבת את הליכתנו בכל מהלך חיינו הארציים, ודווקא על-ידי זה היא מגביהה אותנו לפסגות הרוח. כשנבין ונפנים ונחיה לאורו של יסוד זה, כל היחס שלנו לתורה ולחיים שמסביבנו ישתנה. עלינו להפנים, כי דווקא אם נלך בחוקי התורה – אז תובטח הצלחת תעשיית ההיי-טק, אז נצליח לבנות כבישים ובנינים, אז נזכה למערכת בריאות משוכללת עוד יותר, אז נזכה גם לבטחון אישי ולהורשת האויב מפנינו, אז נחיה חיים שלמים של אומה בארצה על-פי התורה. אז נוכל להעריץ את גדולי ישראל ואותם בלבד, כי הם ייצגו עבורנו את כל מאוויינו הגשמיים והרוחניים. כשנלמד את התורה ונשאף לקיים אותה כחוקת האומה ולא כתורה של יחידים – אז כבר לא יהיה צורך באישים חילוניים שיסדרו עבורנו את הכלכלה ואת שאר צרכי היום-יום. אז הנוער שלנו, וגם המבוגרים יותר, לא ילכו לרעות בשדות זרים, ולא יחושו צורך להעריץ אישים חילוניים, מוצלחים ככל שיהיו. אז נזכה לכבוד התורה ולומדיה באמת.

ע”כ.

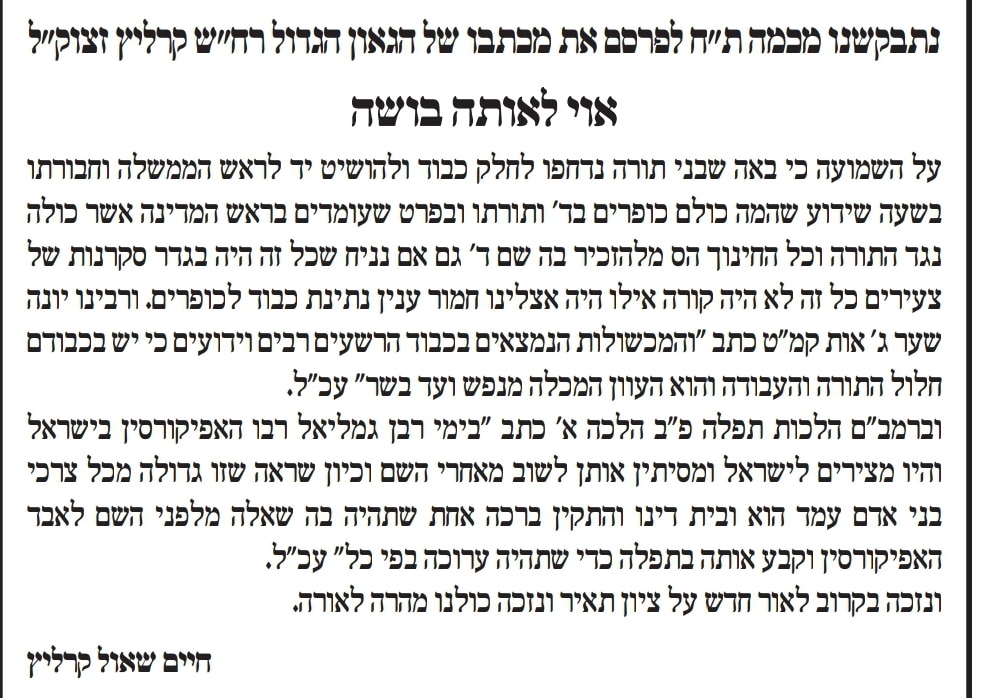

הנה מכתב הגרח”ש קרליץ המדובר:

Jul 4, 2022

פרויקט עדויות ימ״ר ש״י: רכז הנוער של כוכב השחר, מצטיין נשיא, מצא את עצמו נעצר באמצע שירות מילואים ונלקח למרתפי המחלקה היהודית בשב”כ. במשך 12 יום עבר חקירות קשות כשהוא אזוק לכסא, כל זאת על לא עוול בכפו

#עדויות_ימר_שי

*קרדיטים:*

הפרויקט הופק על ידי ארגון ‘חוננו’ ומטה ‘יהודי לא הורג יהודי’

בימוי וצילום: אברהם שפירא וחן קליין

תחקיר: אלחנן גרונר

אולפן, המון סבלנות וקפה: אולפני האפי ג’וז בעופרה

הפקה: כלב בלנק ואליחי שפירא

עריכה: אביטל אביעזר ואביה נתן

You need not wear Tzitzis unless you wear a four-cornered garment.

Rabbi Hirsch (Bamidbar 15:38) finds a beautiful allusion to this in the verses themselves:

דבר וגו׳ ואמרת וגו׳ ועשו להם וגו׳ – כפי שכבר אמרנו (באוסף כתבים, כרך ג עמ׳ קלט–קמ), אילו היה זה ציווי מוחלט, הייתה לשון הכתוב: ״דבר וגו׳ ויעשו להם״ וגו׳. ״ועשו״ מורה על כך שהעשייה היא התוצאה של ״ואמרת אלהם״: הקיום יבוא מאליו, כתוצאה מהוראותיו וביאוריו של משה. אמור להם את כל מה שקדם ואת כל מה שקשור אליו; ועשה אותם מודעים לכך, כדי שישיבוהו אל הלב, ויעשו בשמחה ציצית על כנפי בגדיהם, כפי שאני מצוום.

(Author unknown)