Ezra Chwat: Rambam’s Deliberate Effort to Round Out Mishneh Torah to 1,000 Chapters

A few points I would like to add to Menahem Kahane’s excellent article ‘The Arrangement of the Orders of the Mishnah’, just published in Tarbiz LXXVI pp. 29-40, on the numerological structure of the Mishnah. His point is well taken, that a deliberate effort was made to construct the Mishnah with esthetic or numerological significance.

As would be expected, this has been alluded to in Zohar, Ra’ya Mehimna towards the end of Mishpatim 115a.

In note 44, Kahane raises the issue of the esthetically perfect figure of 1,000 chapters in Mishneh Torah, as part of the Rambam’s explicit intention to create an opus that duplicates the historic impact of the Mishnah (and replace it). Menahem Avidah (Sura II, 1955 267-275) was the first to relate to this feat but omitted the issue of whether this perfect figure was deliberate or not (although stating emphatically that the Divine name formed by the first four words must have been intended). Since, presumably, we cannot read the intentions of the author beyond his explicit statements in the Introduction, this question was apparently not relevant.

Yet in Kahane’s statement, it must be assumed that round figure of a thousand chapters was not the product of the Rambam’s Ruach HaKodesh, (which he never claimed to have), rather a result of an effort to convey an aesthetic value (which we didn’t know he had).

The Genizah has provided us with numerous pages of an autograph draft of Mishneh Torah. The complete collection, with bibliographic details, have been assembled by R. SZ Havlin in the appendix to Machon Ofeq’s Code of Maimonides, the Authorized Version, 1997 pp. 376-407. All but one of these fragments are from the volume Mishpatim.

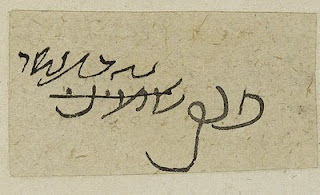

In the page Oxford Bodley Heb. D. 32 fol. 48b we are firsthand witnesses to the change in chapter numbers from the draft of Hilkhot Skhirut to the published edition in which the number at the heading was originally 8, has been crossed through and changed to 11. Subsequently on fols. 51-53 of the same quire we find a chapter numbered “9”, whose content appears in the published edition as two chapters- 12 and 13. The Great Eagle has clearly rearranged the chapter divisions (somewhere between Skhirut 1 and 11) to create smaller but more numerous chapters. This is no easy task because, true to the rules presented in the introduction, he cannot simply split a chapter in two. Similar to the Mishnah, chapter length in Mishneh Torah is clearly and deliberately uniform, enabling for study and retention in regulated, equal daily units.

Apparently, we are witnessing an attempt to create more chapters in order to reach the esthetic (or numerologically significant) round figure of 1,000. If so, it’s not difficult to imagine why the adjustments would be made in Mishpatim, the second to last volume. Rambam never mentions, in the Introduction or elsewhere, this truly outstanding sign of perfection. (Avidah figures that the Rambam was well aware of the thousand chapters but did not flaunt it out of humility). It’s likely that the Rambam did not set out for this goal when he set the blueprint for the Code, or when he projected the scheme of the opus in the Introduction.

But as he reached the end, and the sketches of Mishpatim and Shoftim was already in the draft form, it became clear that to reach the round figure of 1,000 would require only a few alterations. This scenario would have to assume that the volumes of the Yad were composed in an order identical, or close to, the final order of the 14 volumes, leaving Mishpatim near the end.

This finding can shed more light on what we already knew about the criteria for chapter division in MT. Here Rambam is clearly duplicating the criteria of the Mishnah, in which the primary factor is length, whereas subject is at best a secondary element. In Mishnah, a cursory glance at Eliahu Dordack’s subject index tables in the appendix to Mishnah Sdurah, should be sufficient evidence. So too in MT, subjects often cross the boundaries of chapter divisions. In this Rambam differs from the Gaonic monographs where the Qasem or Fasal reflect only the subject matter, allowing one subject per chapter, and one chapter per subject, regardless of length or any other element. This throwback to the literary structure of the Mishnah must have made it possible for the author to rearrange chapter divisions for no better reason than the esthetic 1,000 chapters.

From Giluy Milta B’alma, here.