Peace and Quiet

The pursuit of peace and quiet has been at the forefront of man’s endeavors since time immemorial. The Romans famously achieved this objective in what historians call the pax Romana. Pax is the Latin progenitor of the English word peace, and may also be an ancestor of the Mishnaic Hebrew piyus, “appeasement.” The Jewish People, on the other hand, achieved their pax Judaica under the rule of King Solomon — Shlomo HaMelech — whose very name is a cognate of the Hebrew word for “peace,” Shalom. In this essay we will consider the etymology of the Hebrew word shalom, as well as its counterparts and ostensible synonyms shalvah, sheket, shaanan and shalanan.

King David told his son Solomon about a prophecy that foretells of shalom and sheket under Solomon’s reign (I Chron. 22:9). In explaining that passage, Rabbi Avraham Bedersi HaPenini (1230-1300) writes that sheket implies something greater than shalom. He explains that shalom is the opposite of “war,” but sheket is the opposite of “movement.” In other words, he explains, shalom simply represents the cessation of all hostilities, while sheket implies the complete cessation of any harriedness or toiling that force people to be constantly moving about. In other words, shalom means “peace” and sheket means “stillness.” Rabbi Bedersi ranks the degree of peace/rest implied by shalvah as on par with that of shalom, and explains that sheket implies an even more intense form of peace than those words imply.

Without citing Rabbi Bedersi’s explanation, Rabbi Shlomo Aharon Wertheimer (1866-1935) disagrees on his ranking sheket as connoting a higher form of “peace” than shalom/shalvah. Instead, Rabbi Wertheimer explains that sheket denotes a situation in which there is no outward conflict or discord — but there may be disagreements in the background. Shalom/shalvah, on the other hand, denotes total peace and harmony. A ceasefire that brings a temporary respite to actual fighting can be characterized as sheket, even as “true peace” (shalom) remains elusive.

Why do both Rabbi Bedersi and Rabbi Wertheimer group shalom and shalvah

The answer may lie in their shared etymological roots. Rabbi Shlomo Pappenheim of Breslau (1740-1814) traces the roots of both shalom and shalvah to the biliteral SHIN-LAMMED. He explains that this root primarily means “removed” or “taken away.” This meaning is best illustrated by the verse in which G-d tells Moshe at the Burning Bush, “Remove (shal) your shoes from upon your feet” (Ex. 3:5). Among the various derivatives of this root, Rabbi Pappenheim lists sheol (“grave”) — because in death one is “taken away” from the realm of the living — and shallal (“booty”), which refers to property that looters “took away” from their rightful owners.

In a more positive sense, Rabbi Pappenheim explains that shalvah in the sense of “peace” also derives from the SHIN-LAMMED root, because it denotes a state in which all disturbances or troubles have been “removed” or “taken away.” As a corollary to this import, Rabbi Pappenheim explains that moshel (“ruler”) and memshalah (“government”) are those officials responsible for maintaining a state of shalvah.

As mentioned above, Rabbi Pappenheim also traces the word shalom to the two-letter SHIN-LAMMED root, but takes a slightly different approach in explaining the connection. He explains that the word shalem (“complete,” “finished,” or, in a financial context, “paid”) refers to a state in which everything that had been “removed” from it or “taken away” from it has already been returned, so that nothing is lacking. Something described as shalem is totally complete, and thus requires nothing else to achieve completion. In Rabbi Pappenheim’s estimation, the word shalom too denotes receiving all types of “good” that are required for prosperity, such that nothing extra is lacking.

Elsewhere, Rabbi Pappenheim explains that shalom denotes a lack of friction or dissonance among multiple parties. When all parties live in harmony and agreement, this is called Shalom. G-d is called Adon HaShalom (“Master of the Peace”, Maariv on Shabbat) and Melech SheHaShalom Shelo (“the King that Peace is His,” Shir HaShirim Rabbah 3:14) because He is not comprised of multiple conflicting parts, but always remains in total unity and agreement with Himself. In other words, He is “at peace” with Himself.

At first, Rabbi Pappenheim entertains the possibility that despite their slightly different etymologies, shalom and shalva

Interestingly, the word shalu can sometimes refer to a state of shalvah (see Rashi and Ibn Ezra to Lam. 1:5), and sometimes refers to committing a sin by mistake (see II Kings 4:28, II Sam. 6:7, II Chron. 29:11). In fact, the Targumim typically translate the Hebrew shogeg as shaluta (see also Dan. 6:5, as well as Rashi to Ruth 2:16 and Ramban to Gen. 38:5). How can these two very different meanings converge in one word?

Rabbi Bedersi explains that the complacency of shalvah easily breeds indolence, which causes one not to be careful or mindful enough to avoid sin. Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (to Gen. 8:1, Lev. 5:4) similarly explains that the dual meanings of shalvah/shalu allude to the possible negative aspects of “tranquility.” A person can sometimes become content with his current spiritual stature, such that he no longer strives for greater and greater perfection; instead, he smugly continues in his tried and tested ways. This leads to a lack of spiritual awareness, which can, in turn, lead one down the slippery slope towards sin.

Let’s go back to the word sheket for a moment. This word is often translated as “quiet,” but Rabbi Pappenheim explains that it refers more to the virtues of patience and forbearance. When a person is in a state of sheket, no outside stimulus can get him worked up into a frenzy. He remains calm and serene. Ibn Janach and Radak seem to define sheket as “abeyance” and “calming down” after having been in a more turbulent state.

In a similar sense, Malbim writes that the word shaanan — which typically means “quiet” and “tranquility” (Jer. 30:10, 48:11, Prov. 1:33) — is related to the word shaon (“boisterous din”), but means its exact opposite: “quiet” in that the noisy shaon has been eliminated.

Rabbi Pappenheim explains that shaanan derives from the two-letter root SHIN-ALEPH (or possibly even the monoliteral root SHIN), which means “something uniform/level in which no differences between its various components are apparent.” Words that come from this root can have negative or positive connotations. For example, the words shoah and shayit refer to complete and utter “destruction,” while shaanan refers to complete and utter “tranquility.”

Rabbi Bedersi posits that shaanan implies an even more complete form of peace/rest than sheket does. Rabbi Pappenheim seems to echo this sentiment by explaining that shaanan differs from shalom and shalvah in that it really refers to “calmness” and “serenity” as opposed to “peace.” He explains that one can be in a state of complete shalom, but still be busy or harried with having to tend to the products of one’s prosperity. The term shaanan precludes that type of busyness; it denotes a form of “peace” whereby not only are there no disagreements with others, but one need not even interact with others whatsoever.

Finally, we arrive at the word shalanan, which appears only once in the entire Bible (Iyov 21:23), making it a hapax legomenon. Ibn Janach writes that shalanan means the exact same thing as shaanan, despite the extra LAMMED. However, Radak and Rabbi Pappenheim explain that shalanan is a composite word comprised of shalvah and shaanan.

Besides the words shalom, shalvah, sheket,

Now that’s something to look forward to.

Reprinted with permission from Ohr Somayach here.

My book has two parts:

The first part goes through the entire Tanach and focuses on all the stories in which Avodah Zarah — idol worship — comes up, explaining exactly what was going on in each story. This includes the Golden Calf, Elijah the Prophet’s showdown at Mt. Carmel, and lots of stuff about the Judges and Kings—and Abraham smashing idols.

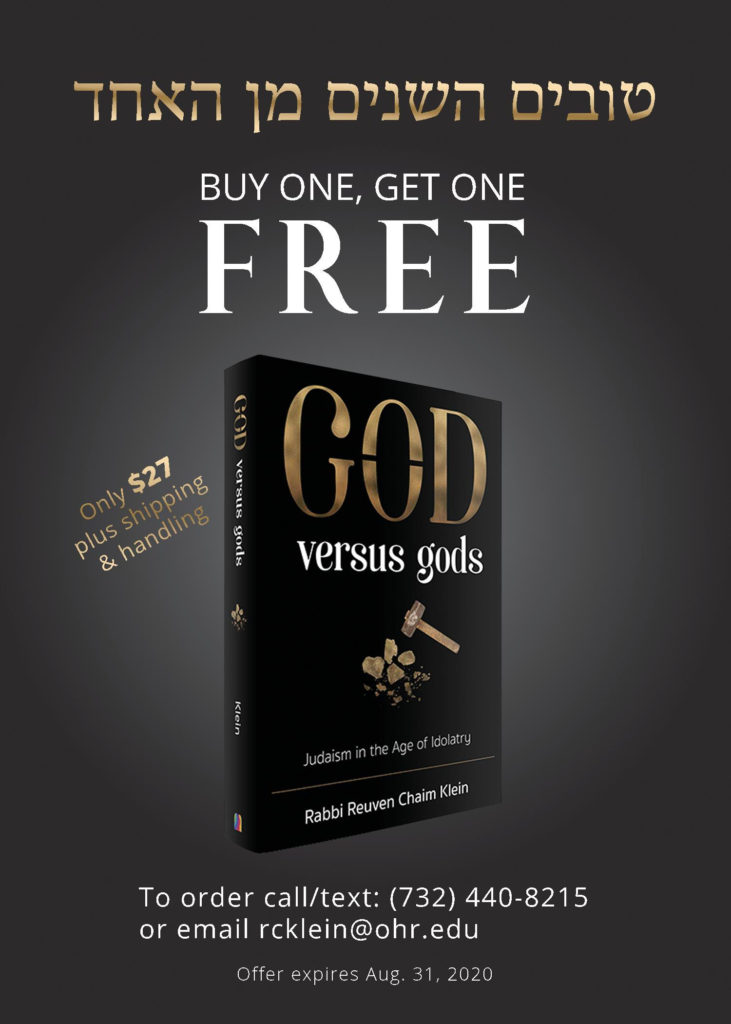

Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein is the author of God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry(Mosaica Press, 2018). His book follows the narrative of Tanakh and focuses on the stories concerning Avodah Zarah using both traditional and academic sources. It also includes an encyclopedia of all the different types of idolatry mentioned in the Bible.

Rabbi Klein studied for over a decade at the premier institutes of the Hareidi world, including Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood and Yeshivas Mir in Jerusalem. He authored many articles both in English and Hebrew, and his first book Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew (Mosaica Press, 2014) became an instant classic. His weekly articles on synonyms in the Hebrew language are published in the Jewish Press and Ohrnet. Rabbi Klein lives with his family in Beitar Illit, Israel and can be reached via email to: rabbircklein@gmail.com